"Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead

Posted : 2 months ago

A quick plug for a little gem of a book that all fans of early radio should know about: "Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead (Cambridge University Press, 1950). It's part of the Modern Radio Techniques series, where a bunch of the technical movers and shakers document the advances that were made during the war, e.g. centimeter radar. This one is about the theory and practice of superregenerative radios. I learned a lot from it and had a lot of fun.

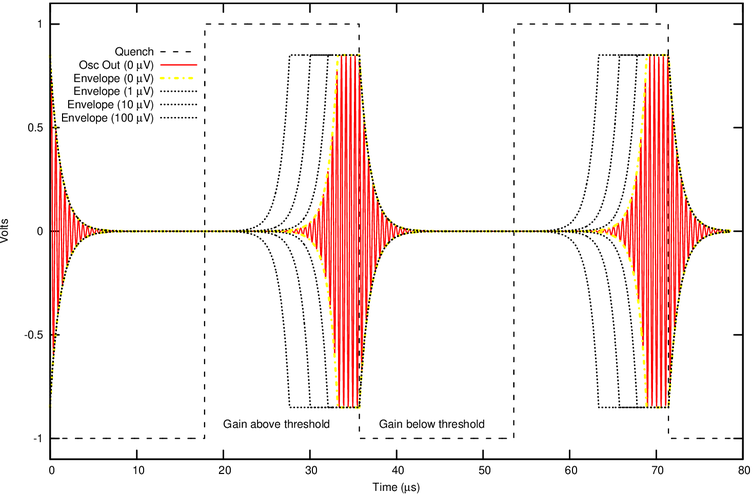

Excursus for folks who aren't early radio buffs (yet): A superregen is an oscillator whose gain is turned on and off at some rate by a quench signal, so that the oscillation repeatedly builds up from noise (and any RF input signal that may be present), as illustrated in Figure 1. The detected signal is the average amplitude of the oscillation. If the gain is high enough that the oscillator saturates in less than the quench ON time, an input signal whose amplitude is e times the noise level, it gives the oscillation a head start of one time constant; if it's e2 times the noise level, two time constants; and so on, so that the average amplitude goes like the logarithm of the total input amplitude (signal+noise). To avoid an annoying squeal in the headphones, the quench frequency is chosent to be above the range of human hearing, i.e. supersonic or (as we now say) ultrasonic. That's where the 'super' in both 'superregenerative' and "superheterodyne' comes from. ('Supersonic' now means something else, of course.)

Figure 1: Logarithmic superregen with square-wave quench. Any in-band signal gives the exponential

growth a head start, so the average amplitude goes like the logarithm of the input amplitude.

Some Highlights:

- The oscillation builds up exponentially with time, so even a low-gain active device can amplify any input signal to any desired degree in a single stage.

- In the classical configuration, a single tube with a gain of less than 10 can amplify the thermal noise at its input to a level sufficient to drive headphones, a good 120 dB worth of gain overall. Its response can be linear or very accurately logarithmic, which I think is amazing.

- The bandwidth of a superregen is set by the value of dG/dt (the rate of change of the net conductance across the tank circuit) when G goes negative (i.e. the quench waveform enters the region of superregenerative gain). Essentially, it samples the input signal from the time the gain turns on, for about one gain time constant. A slower ramp gives a longer sampling time, and hence narrower bandwidth.

- The pulse shape is set by the value of dG/dt when G goes positive again:

- The average frequency of the superregenerative output is not the signal frequency but the free resonance of the tank. (This is fairly obvious because of how LC resonances work.)

- The actual spectrum of the output (over many pulses obviously) consists only of the signal frequency plus sidebands at harmonics of the quench frequency, because the signal injection-locks the superregeneration when it begins--i.e. the superregeneration is actually phase coherent with the signal, even though its average output frequency is different! (That's how superregens can demodulate FM.) The peak of the spectrum is always at the tank resonance, so if the signal frequency is offset from there, the spectrum is asymmetric.

That is so pretty, and (today) so little known, that it should be preserved. I've long hoped to find optical applications of superregens to help with the nasty signal detection problem in the range of 1 pA - 1 uA photocurrents, but so far it's never been quite the right answer. Some more:

- The proof that the pulse shape is Gaussian for sinusoidal quench and exponential for square wave is pretty, and so's the proof that although the frequency of the carrier matches that of the input signal, and the waveform is smooth, it's entirely made up of sums of harmonics of the quench frequency.

- The other proof, which explains the main reason why superregens aren't commonly used now that gain is cheap and spectrum is expensive, is that their noise gain is fairly high--the "sampling" interval early in the quench cycle, determines what the pulse will look like, but is several times shorter than the quench cycle. Thus the equivalent noise bandwidth is that much larger than in a superhet.

Exponential growth and decay is useful for lots of things, e.g. I've used the ring-down of a quartz crystal oscillator as a calibrator for logarithmic DLVAs. [You have to run the crystal at the series resonance, because that's where the mechanical amplitude is greatest. Otherwise you get an abrupt amplitude decrease as soon as you disconnect the oscillator circuitry, before the exponential decay takes over.]

So have a squint and enjoy!

Recent Posts

-

Featured Product: LA-22 Low Noise Lab Amplifier

-

"Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead

"Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead -

Temperature Control 1: Simple Control Theory

-

A High-Performance Time Domain Reflectometer

-

Product Announcement: QL03 Photoreceiver

Archive

2026

- January (1)

2025

2023

- May (1)

2021

- January (3)

2020

2018

2017

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

Categories

- Design Support Consulting (8)

- Expert Witness Cases (15)

- New Technology (1)

- News (33)

- Products (4)

- SED (16)

- Sensitive Design (6)

- Ultrasensitive Instrument Design (27)

Tags

- photon budget (1)

- prototype (1)

- SEM (2)

- microscopy (1)

- microscope (1)

- product (1)

- noise (2)

- ultraquiet (1)

- thermoelectric cooler (1)

- Jim Thompson (1)

- analog-innovationscom (1)

- analog (2)

- ic design (1)

- scielectronicsdesign (1)

- website archive (1)

- MC4044 (1)

- MC1530 (1)

- SiPm (2)

- MPPC (2)

- PMT (1)

- Photomultiplier (2)

- frontend (1)

- module (2)

- hammamatsu (1)

- APD (2)

- SPAD (2)