Featured Product: LA-22 Low Noise Lab Amplifier

Posted: 2 months ago in News, Products, Ultrasensitive Instrument Design

The LA-22 Low-Noise Laboratory Amplifier, 800 Hz–22 MHz, 1.1 nV / √Hz

One problem that comes up again and again in doing measurements is that we need the apparatus to be quieter than the thing we're measuring, ideally by at least a factor of two. Besides quiet, it should be wideband, have an accurately known gain that's flat with frequency, have a clean step response, and generally do its job while keeping itself out of the way. There's a wealth of detail in our app note AN-1 on photoreceiver testing.

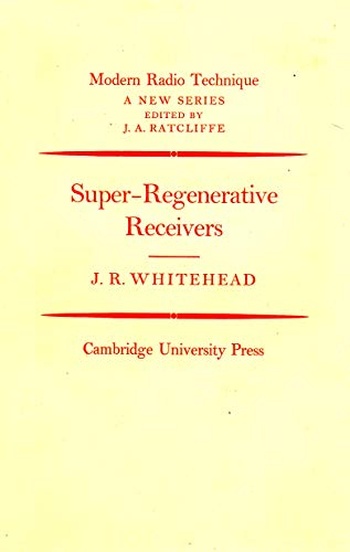

"Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead

Posted: 2 months, 1 week ago in News, Sensitive Design

A quick plug for a little gem of a book that all fans of early radio should know about: "Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead (Cambridge University Press, 1950). It's part of the Modern Radio Techniques series, where a bunch of the technical movers and shakers document the advances that were made during the war, e.g. centimeter radar. This one is about the theory and practice of superregenerative radios. I learned a lot from it and had a lot of fun.

Temperature Control 1: Simple Control Theory

Posted: 2 months, 1 week ago in New Technology, News

Temperature Control

The need to control temperature is everywhere, but getting it right is more difficult than one might expect. A domestic furnace controlled by a simple thermostat keeps a house comfortable in winter, but the inside air temperature swings irregularly over a range of a few degrees. That's fine for a house---you can have a New Year's party, with a bunch of people dissipating a hundred watts each, doors to hot ovens and the cold outside opening and closing, no worries whatsoever. The heating system keeps it comfortable.

A High-Performance Time Domain Reflectometer

Posted: 1 year ago in News, Products

In a previous article, we described an ultralow-cost time-domain reflectometer (TDR) that is used as a radar dipstick for fuel gauges in heavy equipment. Its 150-ps edges were better than good enough, and its rock-bottom BOM cost ($1.30 @ 100 pcs) made it possible for the whole gauge to retail for under $40. That performance is far from the limit for low-cost samplers, as we'll see.

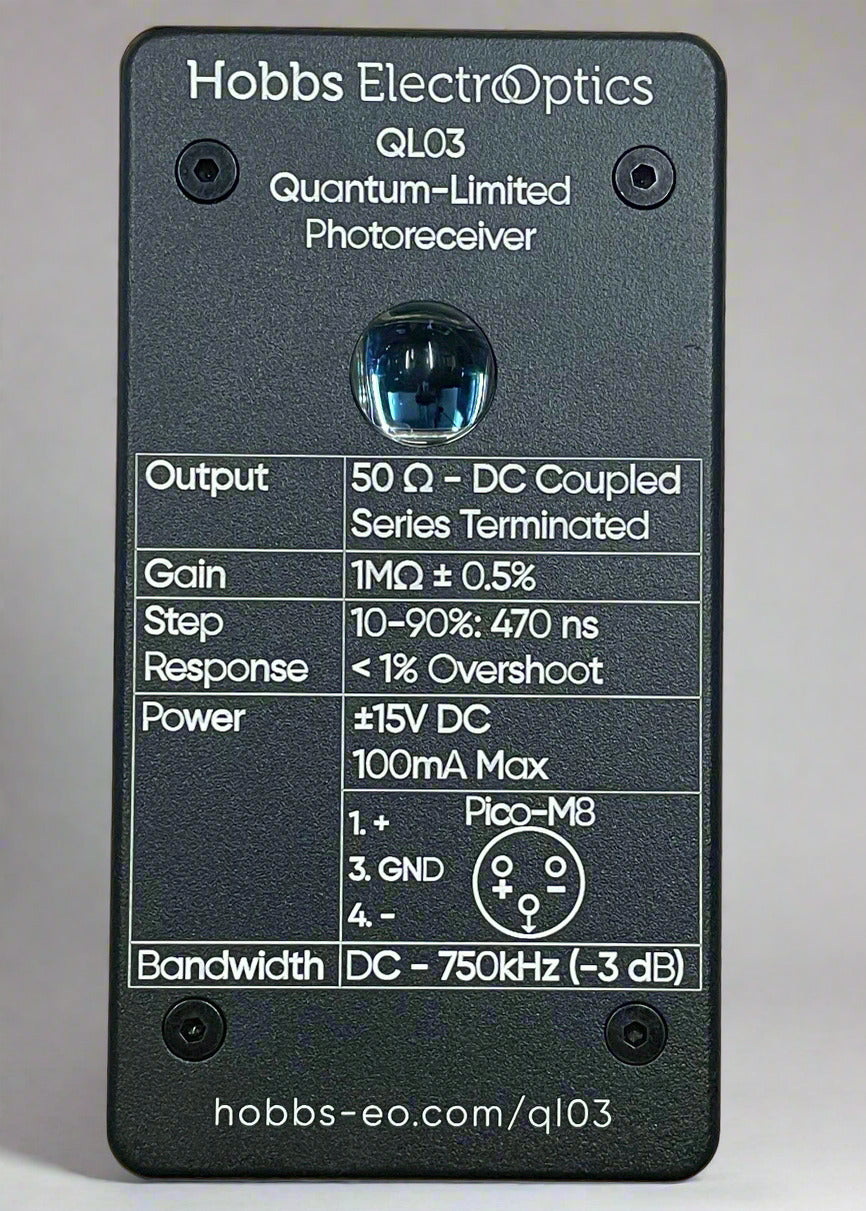

Product Announcement: QL03 Photoreceiver

Posted: 1 year ago in News, Products

Recent Posts

-

Featured Product: LA-22 Low Noise Lab Amplifier

-

"Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead

"Super-Regenerative Receivers" by J. R. Whitehead -

Temperature Control 1: Simple Control Theory

-

A High-Performance Time Domain Reflectometer

-

Product Announcement: QL03 Photoreceiver

Archive

2026

- January (1)

2025

2023

- May (1)

2021

- January (3)

2020

2018

2017

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

Categories

- Design Support Consulting (8)

- Expert Witness Cases (15)

- New Technology (1)

- News (33)

- Products (4)

- SED (16)

- Sensitive Design (6)

- Ultrasensitive Instrument Design (27)

Tags

- photon budget (1)

- prototype (1)

- SEM (2)

- microscopy (1)

- microscope (1)

- product (1)

- noise (2)

- ultraquiet (1)

- thermoelectric cooler (1)

- Jim Thompson (1)

- analog-innovationscom (1)

- analog (2)

- ic design (1)

- scielectronicsdesign (1)

- website archive (1)

- MC4044 (1)

- MC1530 (1)

- SiPm (2)

- MPPC (2)

- PMT (1)

- Photomultiplier (2)

- frontend (1)

- module (2)

- hammamatsu (1)

- APD (2)

- SPAD (2)